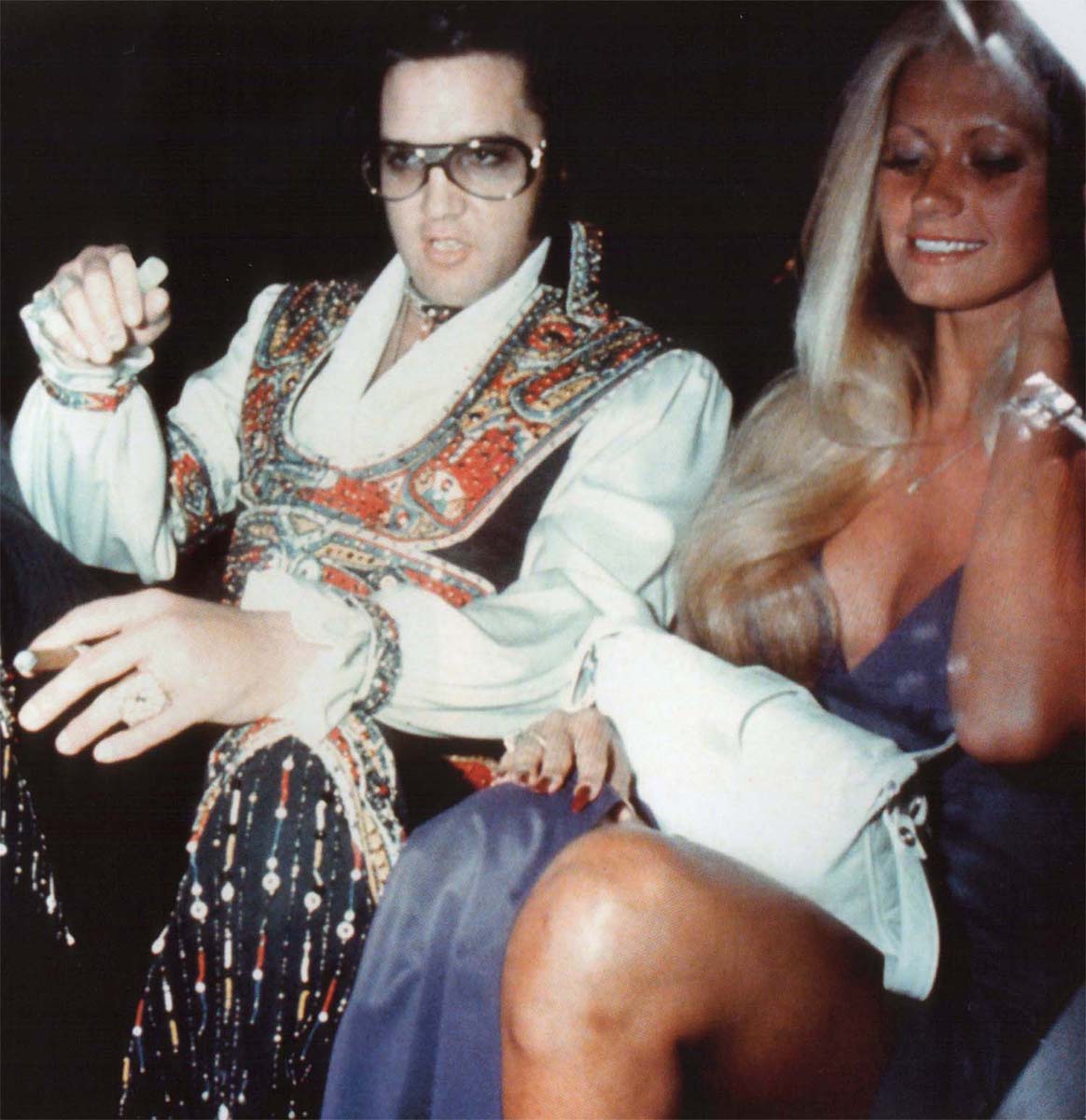

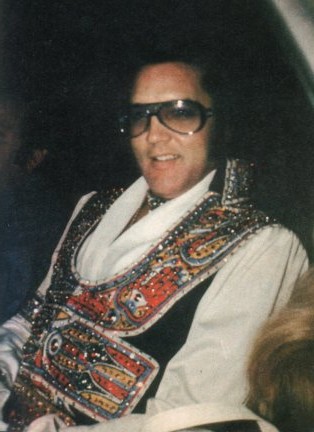

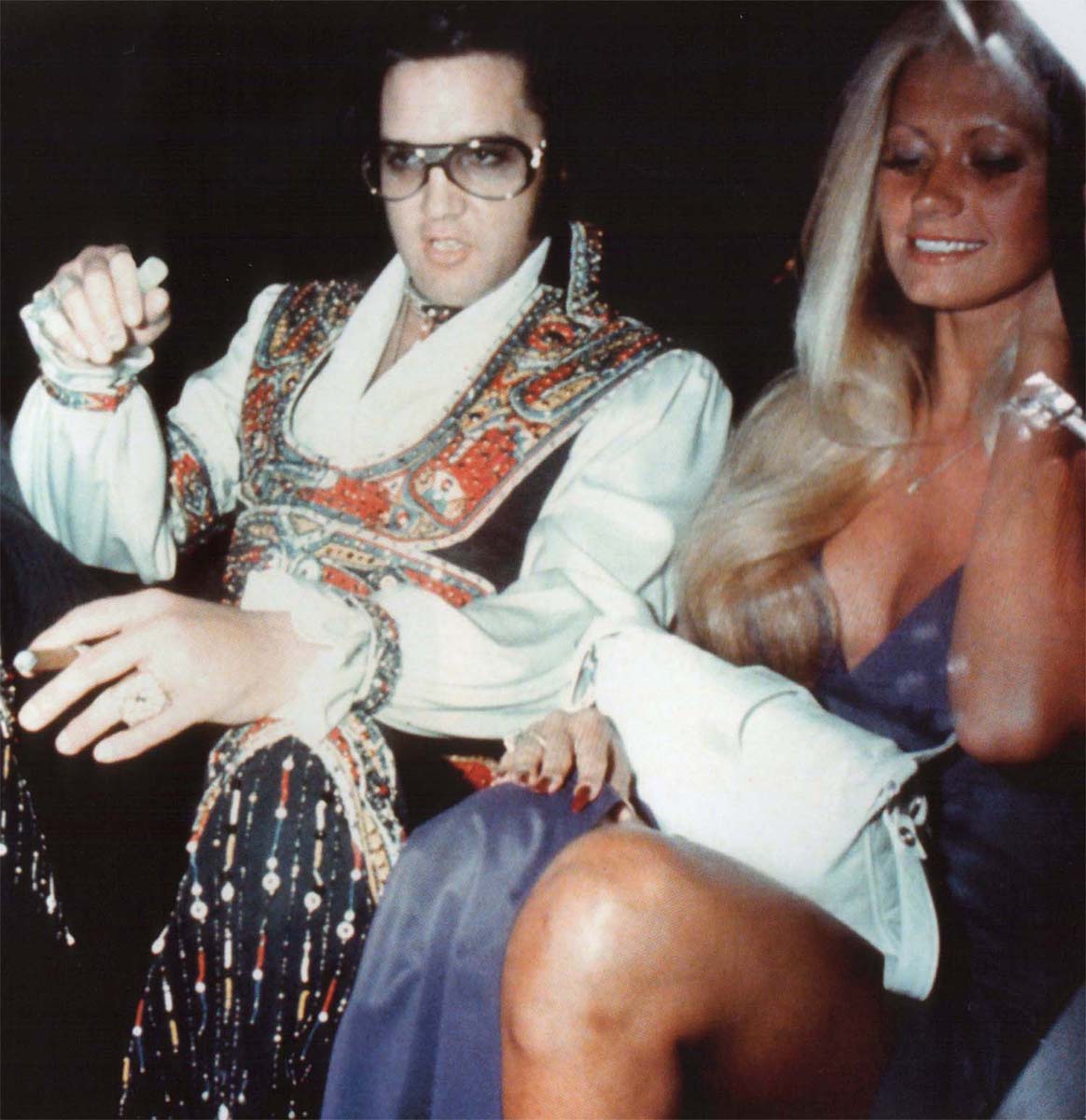

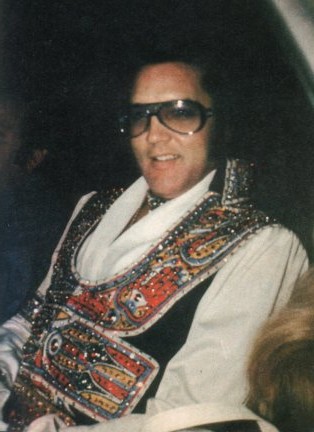

Looking great getting into his limo on the way to perform the evening show in Uniondale, NY on July 19, 1975 - notice the glow stick in his hand in a couple of the photos

Later at the show Elvis still has the glow stick in his hand

Thanks to E-Cat for some of the photos

Elvis Presley

Nassau Coliseum, Long Island

19 July 1975

Nick Cohn

Elvis had two years to live but already seemed a dead man walking. When I saw him in Las Vegas the year before, he'd been robotic. A crash diet had slimmed him down, temporarily, to something close to his youthful shape; it had also drained him of all energy. In Vegas, he sleepwalked through his old hits, often trailing off halfway through a verse to launch into dark, incoherent mumblings. Only on 'How Great Thou Art' did he cast off a sense of creeping dread. At the final bellowed line - 'O my God, how great thou art' - his voice turned raw and harsh, and he sounded like a great wounded beast, stumbling towards oblivion. When the house lights went on, most of the people around me were in tears.

Afterwards, I felt this was my last Elvis show. I'd loved him since 'Heartbreak Hotel', kept the faith through all his subsequent highs and lows, but I could no longer stand to watch him self-destruct.

It took the sneers of New York's hiperati to change my mind. In '75, Dylan and the Stones were the reigning gods of the rock establishment, Springsteen its new rising star. Elvis was seen as ancient history, a curiosity at best. Instead of Madison Square Garden, he was reduced to playing Long Island, an hour's drive and light years from Manhattan. A publicist for 10cc called him a circus freak. I wasn't having that.

It was a broiling night. Nassau Coliseum, an arena most often used for hockey games, felt like a Turkish bath. If you bought a souvenir programme or poster, it stuck to the fingers like glue, and the crowd made use of this, holding up pictures of Elvis like religious artefacts. As the lights dimmed and the theme from 2001: A Space Odyssey sounded, announcing the King's arrival, a sea of ghostly images of his lost youth and beauty greeted him

The sacramental spirit was typical of Elvis shows in his final phase. His audience - families from grandmas to babies, bottled blondes of a certain age, working stiffs and their wives - didn't come simply to be entertained but to share in an act of communion. Richard Nixon's silent majority, they used their idol's life to channel and bear witness to their own; to relive first loves and marriages and divorces, glory days and wreckage alike. It was no coincidence that Elvis had spent his childhood Sundays at Holy Roller services. There was something Pentecostal about his stage presence. Even in ruins, drug-addled and bloated, he made the faithful feel blessed.

This night on Long Island, though, he was no ruin; certainly not the zombie I'd seen in Vegas. He'd packed on major poundage, his moon face had lost all definition, and there was no mistaking the corset straining to hold in his gut, yet he seemed reborn. Maybe he'd hit on a new cocktail of pills, or maybe the off-stage turmoil I'd heard was threatening to wreck his tour had whipped him to a froth. Either way, he charged out on stage like a man primed to do or die.

His outfit, even by his standards of overkill, was ludicrous. Midnight blue bell-bottoms and a plus-size sequined belt were set off by a suit-of-lights matador jacket, a rhinestone dazzle of crimson and blue and gold. Blackpool illuminations had nothing on him. Still, as he struck a karate pose that almost exploded his corset, he launched into 'Big Boss Man' with a fire and attack I hadn't heard from him in years and didn't expect to hear again.

Memories of his 1968 TV special, his last great triumph, and a time when his guitarist James Burton had described him to me as 'a lean, mean, killing machine', flooded back. Lean and mean might be out the window, but the killing machine was up and pumping. Even the Fifties' medley, which he usually threw off like used Kleenex, struck sparks. I've never seen a man sweat so hard, he seemed to be washing away. Though I won't pretend to recall every song, I can still hear his balls-out, almost brutish revamp of 'Hound Dog' and the limpidity of 'I'm Leavin', aching with futile regrets.

At first, the audience wasn't quite sure how to respond. It was almost as though a loved one on life support had suddenly ripped out the tubes, disconnected the oxygen tent, and started doing cartwheels up and down the ward - thrilling, yes, but we were also fearful, half-expecting him to collapse. It took time before we trusted our eyes and ears, and started to exult.

More than 30 years later, I see Elvis clutching an outsize toy duck that someone has thrown to him; swiping at his eyes, trying to swat away the floods of sweat; and down on one knee, head bowed and arms flung wide, soaking up our adulation, then struggling to rise again. And I see him reaching down to the front row, handing out bright-coloured scarves and accepting kisses in return. He makes his way to the end of the row, where he's confronted by a chic model type in dark glasses, who doesn't offer a kiss but a sneer. Obviously, she finds him absurd, a sad old man. Elvis feels this and recoils. He makes an indeterminate motion of his right hand, hard to say if he's pleading with her or cursing her out, before turning his back. The show resumes. Elvis is still impassioned, but now there's a note of desperation, something haunted. After a few minutes, he sits down at the piano and starts to sing 'You'll Never Walk Alone'.

It's a song I despise, but Elvis clearly loves it. Years later, I'll read that Roy Hamilton's 1954 version was a major inspiration in making him a singer. At any rate, he tells us he's always wanted to perform it on stage. Tonight's the night.

Instead of the triumphalism of Gerry Marsden and the Kop End, he treats the song as a private meditation, full of pain and the yearning to believe. Though the lyrics speak of hope, Elvis turns them into a cry, as if reaching for one last sliver of light in engulfing darkness. I am alone, he seems to be saying. All of us are alone. But maybe, just maybe, we can find someone or something to cling to. In his case, it's God. But each of us, hearing him, reaches for our own salvation.

Elvis playing You'll Never Walk Alone that night

The rest of the night is a blur. Objectively, I have seen better shows - Jimi Hendrix at the Savoy, Prince at the Ritz, James Brown (more than once) at the Apollo, and Johnny Paycheck at the Acadia County Fair, to name just a few. None chilled me as profoundly as those few minutes of Elvis alone at the piano, singing a song I can't stand. If great art needs nakedness, it was the most naked performance I've ever witnessed.

Nik Cohn's latest book is Triksta: Life and Death and New Orleans Rap (Vintage)